This

June, David Smith opened a Haight-Ashbury Medical Clinic. At the time,

some 300 young people were coming into San Francisco each day. Instead

of welcoming the visitors or preparing for their problems, the city's political

leaders were encircling the Haight-Ashbury with police, hoping to "starve"

its young community. Dr. Dave disagreed. He believed the kids could not

he wished, or willed, away. "The Haight-Ashbury is a great experiment in

modern living," he said at a news conference. "These young people constitute

a minority group, and as such. They deserve special treatment. Health services,

like love, should not be conditional." This

June, David Smith opened a Haight-Ashbury Medical Clinic. At the time,

some 300 young people were coming into San Francisco each day. Instead

of welcoming the visitors or preparing for their problems, the city's political

leaders were encircling the Haight-Ashbury with police, hoping to "starve"

its young community. Dr. Dave disagreed. He believed the kids could not

he wished, or willed, away. "The Haight-Ashbury is a great experiment in

modern living," he said at a news conference. "These young people constitute

a minority group, and as such. They deserve special treatment. Health services,

like love, should not be conditional."

Smith operates his seven-room clinic above a Haight-Ashbury store. His

visitors sit on shipping crates and well-worn chairs. His medical supplies,

donated by some of the nation's biggest pharmaceutical companies, fill

one small closet. Psychedelic drawings, personal messages for runaway and

lists of badly needed supplies liven the walls. A 30-year-old ex-businessman

supervises volunteer "nurses" from the community Doctors and University

of California medical students drop in to help. A sign on the door reads:

"Haight-Ashbury Medical Clinic Loves You." hundreds of drug users and abusers

have come through that door in past months. Still more are learning that

members of the medical profession do care about young people with problems,

even though present laws brand them a felons.

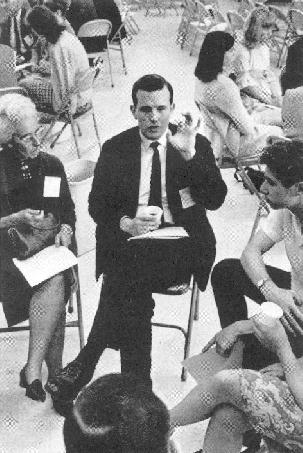

Like many doctors, David Smith does not believe in "sinners." He does

believe in sickness and in education as an effective cure. He talks on

television panels. Lectures parents and their children in the suburbs,

arguing that scientific facts are the best antidote to drug myths. He warns

the young against false prophets and untested drugs, whether designed to

expand consciousness or cure the common cold. And he is no less vehement

with parents. "How," he asks suburban mothers, "can you expect your children

to respect authorities who will ruin a person's life for possession of

marijuana or put a man in jail for using a drug with the abuse potential

of a cocktail? Police tell young people that smoking pot will turn them

into addicts. The kids know it's not true. They figure they've been handed

lies about other drugs as well, and go on to try them. We can earn their

respect only by telling them the truth and treating drugs as medical, more

than police, problems."

Smith also is pushing further into pharmacological research with many

of his former professors. Together, they are trying to stay ahead, or at

least abreast, of the new drug products of the underground. Recently, they

found young people using STP, which gives a three-to-four-day bad "trip."

"This points up the value of acting, rather than reacting to a problem,"

Smith reports. "We found STP before it spread, and could warn kids and

doctors. But we are still far from an antidote." One reason is that Federal

and state laws seriously inhibit drug-testing, and although Smith has received

increasing encouragement and offers of financial aid from the city Public

Health Department, his clinic lacks the full support of many parents and

politicians. So far, the doctor has walked a tightrope between two generations.

He can keep his balance and hold open his lines of communication only if

young and old will follow his lead in refusing to take sides. "We can work

our problem out together," David Smith says. "We can't afford to fight."

END |